Mary McRae sailed for New Zealand on the emigrant ship “Hydaspes” in 1872. Recently widowed, she took with her her four sons and three daughters, and her memories of her 45 hard years in the Kintail district of the North-West Scottish Highlands, territory which was the MacRae heartland. She also took with her a wooden box marked “Household Goods”, which contained one of the most essential household items in Kintail at that time. This was a fine copper and brass whisky still, which was to have a colourful history once it was reassembled on her new holding in the Hokonui hills of Southland in New Zealand’s South Island.

She left behind in Kintail a conviction for illegal distilling which had attracted to her, or rather to her son Duncan, a massive £650 fine, with an additional £150 for non-appearance at court for operating a still on Kishorn Island in Kintail. Mary’s husband had died the year before and, possibly, dire economic necessity had driven her to illicit distilling to support her large family, as it did many others. There is no record of the fine being paid before Mary left Scotland, indeed such a sum would have been impossible for a poor Highland crofter to find.

She left behind in Kintail a conviction for illegal distilling which had attracted to her, or rather to her son Duncan, a massive £650 fine, with an additional £150 for non-appearance at court for operating a still on Kishorn Island in Kintail. Mary’s husband had died the year before and, possibly, dire economic necessity had driven her to illicit distilling to support her large family, as it did many others. There is no record of the fine being paid before Mary left Scotland, indeed such a sum would have been impossible for a poor Highland crofter to find.

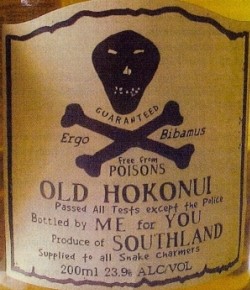

The McRaes (most dropped the first ‘a’ on arriving in New Zealand) settled in the Southland district which was heavily populated by Scots, particularly Scots Highlanders, with many hundreds from Kintail itself. The locals still universally spoke Gaelic, played the classical bagpipe (piobaireachd) and had a taste for whisky – which was very expensive if imported. There existed a local hooch produced from the Cabbage Tree, but this deadly brew was more of a rum than a whisky and Mary soon found a ready demand for her craitur when she started distilling again with her sons. At events in the local Celtic Society Hall and as far away as Invercargill at the Caledonian Sports Society’s Games, the Hokonui brand soon found a market.

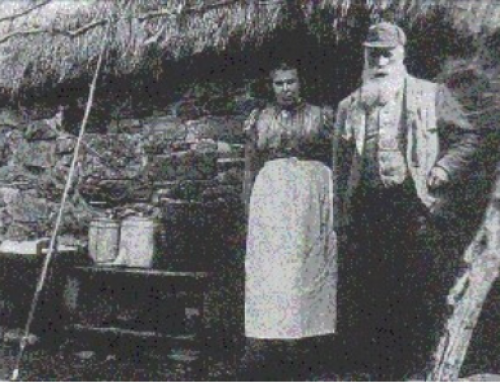

This was still frontier time in Southland and the authorities could only make limited efforts to control illicit stills of which there were many besides Mary’s. On one occasion, officers came to her cabin and listened at the window to the conversation for clues. As the talk inside was all in Gaelic, they went away as mystified as when they came. On another occasion, the customs officers might have been more lucky had Mary (now known as the cailleach, old woman) not sat down over a whisky barrel, covering it with her skirt and remaining seated all the while the exciseman made his search. Mary died in 1911 at the ripe old age of 92 and she attributed her lifelong good health to a daily dose of her own dram. In the years after the First World War, however, the frontier epoch had passed away and the more resourceful authorities took a more active role in eradicating illegal whisky distilling in Southland where many stills, including Mary’s own, were still in operation. One law enforcement official said: “Southland is absolutely notorious for the distillation of whisky, which everyone knows had been carried on here for more than 50 years.”

The first successful prosecution was in 1924 when Alex Chisholm and Alexander McRae were fined $200NZ (£100) for operating an illicit still. Then in 1928 came the Awarua case when another illicit still was found and smashed, and a similar fine imposed to the case four years previously. But the cailleach’s own still was still bubbling away merrily. One Duncan “Piper” McRae (no relation) had married the cailleach’s daughter and he carried on the production of whisky with her still, which then passed through farther generations of the family. By 1928 intermarriage had brought it into the hands of Duncan Stuart who operated the still at Otapiri Gorge. Stuart was producing on a large scale and it was his main employment. According to the Customs Department, he was making 10 gallons of whisky a month, representing a loss in customs revenue of $1260 a year. Selling the whisky at $4 a gallon brought him $10, the equivalent of £5 a week, a tidy income in the 1920s. A massive fine of $1000 and confiscation of the still meant an end to the life of the equipment which had operated in Southland for almost 60 years and for an untold number of years in Kintail before that. However, there was one more chapter in the Southland whisky saga before it became history.

One of the problems facing excisemen in Southland was the thick cover of bush. This meant that smoke from the stills became dispersed through the leaf canopy and difficult to spot. Knowing there were stills operating in the Dunsdale area of Southland, the excisemen came up with a novel idea, aerial surveillance, by which they might hope to discern the dispersing clouds of smoke.

John Smith was the instructor with Southland Aero Club and the Collector of Customs chartered him and his Gypsy Moth in 1934 to overfly the bush around Dunsdale where another family of McRaes, William, father and son, were under suspicion. Now this family of McRaes had a reputation! Back in the 1890s, John McRae, also a whisky maker, had been accused of murder in a very murky case involving whisky and women. Though he had been acquitted, here was clearly a family not to meddle with. Smith later recalled how he earned his fee, but avoided any personal problems: “He (the customs official) went straight up to the wall map and pointed out the spot where the still was set up and said ‘You know what to do.’ I knew what would happen if I flew over that place, it would be a bullet first and questions afterwards. There was a west wind blowing and I took the collector all around the Hokonuis till the turbulence made him ill, but I never went anywhere near that still.” Eventually, though, the excisemen found the still, which McRae had set up just outside his farm on Maori Reservation land. When challenged he said: “If it is outside my boundaries, I would not know anything about it.” Indeed, the evidence against the McRaes was mainly circumstantial and, when brought to court, they were discharged by the jury. The police, however, wrecked the still and this was really the end of the sixty or more years of the Hokonui blend.

The story of the illicit distillers of Southland has been a lifelong obsession of Bill Stuart, and in 1982 he brought out a fascinating book on the topic, Satyrs of Southland. Since then, his indefatigable efforts have borne further fruit in the establishment of a Hokonui Whisky Centre in which tells the story of the McRaes in particular. For his work, Bill and his wife Lisa where given a lifetime pass to the Centre. It is a pity that visitors cannot taste the Hokonui brand there, as reports of consumers in the past testify to its excellence. “It was just like whisky”, said one, and what higher praise could there be?

This article was published in Issue 60 of Whisky Magazine