Just around 1840, the time when William Rutherford was setting up his cellars in Niddry Street, Edinburgh (see Rutherford and the MacRaes), his distant kinsman Alister Mhor (Alexander MacRae) was building a new home for his family on a tiny island close to the shore of Loch Monar, high above Strathfarrar, on the old drove road that crossed the mountains between Beauly and Kintail.

Forced out of the traditional clan homelands of Wester Ross by famine and land hunger, Alister took advantage of the ancient law that gave him squatter’s rights if he had his house built and the lum reekin before the landowner attempted to move him on.

Assisted by his wife, he soon had constructed a simple dwelling following the local tradition, constructed of rough hewn boulders, with a stout heather thatch roof and complete with smoking chimney! It consisted of only two rooms and at the end a byre for the cow. They cleared a small area of the mineral rich ground and grew barley and potatoes and, once their presence had been accepted by the laird, constructed a causeway linking the island to the shore at Pait.

Although he grew some barley, the ground around his cottage was rough and stoney and it must have been a struggle to cultivate. He found it much easier to barter for grain with the farmers down the glen, not much chance of money changing hands there! Porridge, potatoes and fish from the loch constituted their diet, together with what game they could acquire without upsetting the laird.

People had been distilling their own spirit for generations, using their acquired or surplus grain to produce whisky to warm away the cold winter nights with a little left over to sell on to their neighbours. Government legislation had now banned this practice, restricting whisky production to the new licensed distilleries and folk like Alister saw a new career beckoning! He set up his illicit stills in a little bothan by the burn at Cosaig, not far from the edge of the loch and was soon in full production. Before long, his whisky was being distributed throughout the district and even the laird became an established and satisfied customer!

His stills were housed in a little bothan by the burn at Cosaig, not far from the edge of the loch, handy for Alister but also handy for the gaugers. These excise officers scoured the wild countryside for illicit distillers and it was not long before a large group found Alister hard at work. They arrested him and marched in triumph to Dingwall, but there was no shame in being caught distilling illicit whisky, an activity that had been an essential part of Highland life for hundreds of years.

Convicted and fined, he returned to the cottage at Pait determined not to be caught again. He rebuilt his stills in a new and more remote location, high on the slopes of Meall Mor and it was here that his son Hamish Dhu learnt his trade. Long before his father died in 1887 at the age of 97, Hamish had surpassed him with his skills and his Pait Blend was renowned as a whisky of the highest quality. Regarded as superior to many of the licensed whiskies it was much sought after from Kintail to Inverness and, of course, being duty free it would also have been much cheaper!

Convicted and fined, he returned to the cottage at Pait determined not to be caught again. He rebuilt his stills in a new and more remote location, high on the slopes of Meall Mor and it was here that his son Hamish Dhu learnt his trade. Long before his father died in 1887 at the age of 97, Hamish had surpassed him with his skills and his Pait Blend was renowned as a whisky of the highest quality. Regarded as superior to many of the licensed whiskies it was much sought after from Kintail to Inverness and, of course, being duty free it would also have been much cheaper!

When they died, both father and mother were carried back over the hills to Kintail for burial in the traditional manner, with relays of men taking turns to carry the coffins. Mother seemed to have been of particularly sturdy build as one member of the party remarked she was a big heavy woman! However, an essential part of the tradition was an abundance of whisky, before, during and after the journey and there are stories of other burials when coffins were dropped down the hillsides by inebriated bearers! One lady of much slighter build than Hamishs mother was found still laid out on the kitchen table when a well refreshed funeral party returned after carrying her empty coffin many miles and interring it in the family grave.

Much of Hamishs distilling took place during the long winter months when snow made it hard for the gaugers to travel but they did make at least one excursion up the loch by boat, looking for telltale wisps of smoke on the hillside. No doubt the considerable local support that the MacRaes enjoyed had resulted in the boat being delayed and a warning sent ahead. On another occasion, the excisemen were persuaded to enjoy the local hospitality at Ardchuick while on their way to apprehend Hamish. The next morning they were unable to continue on their mission, ill as the result of drinking bad whisky, and they dragged themselves back to Dingwall. Hamish went to great lengths to assure the district that the bad whisky was not of his making!

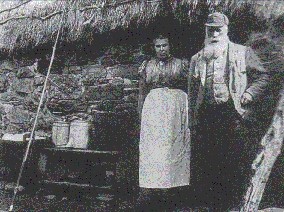

Hamish and his sister Mary were by now getting older, the stills were worn out and the increased activities of the excisemen made operating increasingly difficult. His father had been a large and well proportioned man of exceptional strength with a reputation for being wild when roused and the gaugers had been more than a little wary of him. Although Hamish was of similar build and strength, the excisemen had become more organised and better resourced and he was not regarded with the same apprehension that his father had been.

Hamish and his sister Mary were by now getting older, the stills were worn out and the increased activities of the excisemen made operating increasingly difficult. His father had been a large and well proportioned man of exceptional strength with a reputation for being wild when roused and the gaugers had been more than a little wary of him. Although Hamish was of similar build and strength, the excisemen had become more organised and better resourced and he was not regarded with the same apprehension that his father had been.

In 1901 Hamish decided on a final twist of the gaugers tail. He reported the finding of a still (his own!) and after leading them to the site he claimed the £5 reward offered by the Government and retired from what most highlanders regarded as an honourable trade.

He was a larger than life character, much liked and well respected in his community. Despite his very basic way of life, he would regularly don full Highland Dress on a Sunday and visit the laird for a dram and a blether. When he died in 1915 he was taken home to the ancient burial ground at Clachan Duich in Kintail, where he lies beside his Father, Mother and Sister.

Although it was a popular whisky in its time, it is unlikely that the Pait Blend would have appealed to the palate of today. Our 21st century dram must, by law, be matured for a minimum of three years in oak casks before it can even be called Scotch Whisky. In practice, most whiskies are matured for considerably longer than that to allow the flavours to develop and the rough edges to be smoothed off.

Hamishs whisky would have been sold and drunk as soon as he could distribute it. In the difficult winters, he might have been able to build up some stock, and that stock might have been allowed to age for a few months, but most whisky would only be a matter of weeks old when it was consumed. It would have been a rough, fiery and very powerful drink with considerable character! The same adjectives might have been used to describe our ancestors, James Hamish Dhu MacRae and his father Alister Mhor!

But the Pait Blend did not die with Hamish Dhu. Hamish and Mary had a younger brother, Alexander Andrew, who had been born at Pait in 1857. Alexander and his wife Christina left Scotland to make a new life in New Zealand and were joined in Southland by a number of cousins, one of whom brought with her Alister Mhors recipe for making whisky. When prohibition was introduced to New Zealand in 1902 the MacRaes once again saw opportunity beckoning!

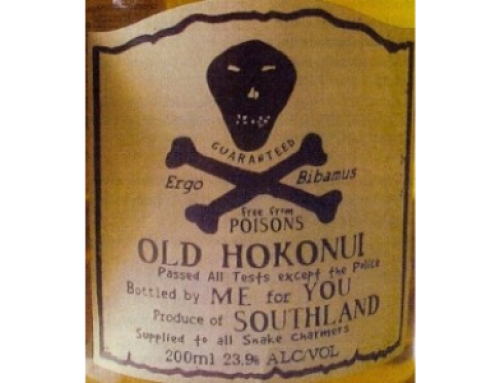

Soon, the family was hard at work supplying not only the community but also the local constabulary with Hokonui moonshine. Some 51 years and over 30 prosecutions later, the making of whisky was legalized and today visitors to the Hokonui Moonshine Museum in Gore can not only learn the story of the MacRaes tradition of illegal whisky making in New Zealand but can purchase a bottle of Old Hokonui whisky, still being made to Alister Mhors original recipe!